How Old is That Bear?

One of the most common questions we get when visitors see a bear in Yosemite is, “How old is that bear?” Knowing a bear’s age can help us understand a lot about its behavior and how to manage it. If a bear has been managed since it was young, we know exactly how old it is. If bears are first captured when they are older, biologists use tooth wear as an indication of a bear’s age. Determining if the canine teeth are worn, the level of wear on the incisors, and the presence or absence of dentine spots, all place the bear into a certain age category. Bears are classified as either a cub (<1), yearling (1), sub-adult (2-3), new adult (4-7), middle-aged adult (8-15), or old adult (16+).

Bears are omnivores and eat both plants and meat, and their jaws are a combination of sharp canines and flat molars. From chewing grass, to cracking acorns, to eating carrion, a bear’s teeth are essential to their survival. As a bear ages, their teeth become worn down, rounded, and discolored.

Young bears, like yearlings, have no dentine spots. Teeth are white and canines are sharp and pointed. Photo: NPS

Older bears, like the this adult female captured in November 2018, have yellowing teeth and rounded canines. She is currently the oldest known tagged bear in the park at 21 years old. Photo: NPS

This bear still shows signs of good health despite her tooth wear and has been denning since December 2018. Worn teeth make it increasingly difficult for a bear to chew natural foods, and can lead to conflict with humans if a bear obtains human food that can give a bear a much easier intake of calories.

You can help us keep these and other wildlife wild and healthy by always keeping your food stored properly when in bear habitat and respecting all wildlife by keeping your distance.

How Technology Has Helped Yosemite’s Human-Bear Management Program Hit All-Time Low Bear Incidents

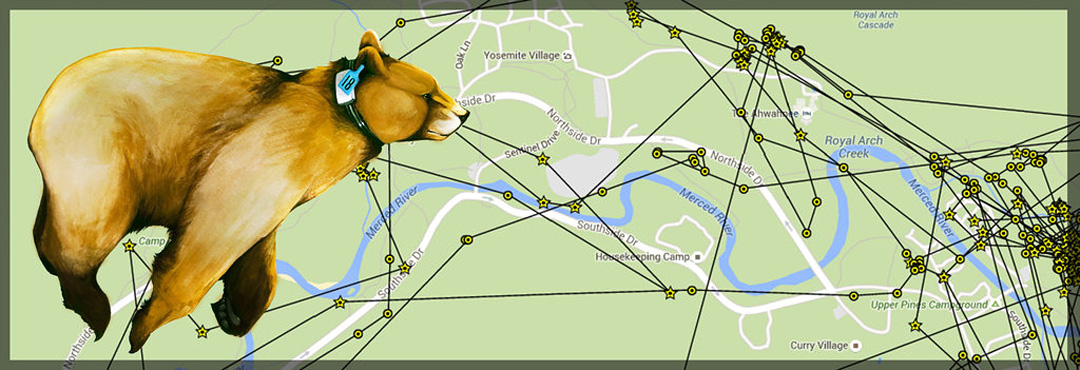

Photo: Josh Helling

Yosemite has a long and tedious history managing bears, people, and the interactions between the two. In 1998, the park hit a record high number of bear incidents in the park with over 1,500 (documented) incidents in one year. This was a huge turning point for the park in changing the way that we managed our bears, and more importantly, people. Beginning in 1999, massive efforts to provide public information and education regarding bears and food storage, along with improvements to the park’s bear-resistant food storage and garbage disposal infrastructure greatly reduced availability of human foods to bears and educated millions of visitors. Additionally, individual bears were managed more directly/rapidly with an intensive program to scare them away from development using anything from yelling to less-than-lethal shotgun rounds. These efforts resulted in quick and major improvements to human-bear conflict. But still, the number of bear incidents remained in the hundreds each year for well over a decade.

With the use of technology, incidents have now been under one hundred per year for over four years. This year we’ve hit a new record low, with only about 22 bear incidents total for 2018. If you want to learn more about how the park used technology to further reduce bear incidents, you are in luck! There is a new journal article out describing how technology was used in Yosemite’s Human-Bear Management Program to bring the number of human-bear conflicts in the park to new record lows.

Mazur, Rachel L.; Leahy, Ryan M.; Lee-Roney, Caitlin J.; and Patrick, Kathleen E. (2018) “Using Global Positioning System Technology to Manage Human-Black Bear Incidents at Yosemite National Park,” Human–Wildlife Interactions: Vol. 12 : Iss. 3 , Article 8.

Available for download at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/hwi/vol12/iss3/8

Empty Yosemite – Bears Take Back Yosemite Valley During the Ferguson Fire

On July 13, 2018, the Ferguson Fire started in the Merced River Canyon just west of Yosemite National Park. At the time the fire started, the park was experiencing peak season visitation and biologists were monitoring up to 20 different bears foraging naturally in Yosemite Valley on a daily basis. Yosemite Valley and some other areas closed to visitors from July 25 to August 14 due to health and safety concerns. Employees and residents were also evacuated for part of that time, leaving only firefighters and emergency personnel behind. Consequently, Yosemite Valley was unusually empty and exceptionally quiet. As a result, bears immediately began frequenting many areas normally teeming with people during bustling summer days.

Black bears are naturally curious, but shy away from people. They generally use corridors of forest cover to make loops around their home ranges in Yosemite Valley while searching for food. As opportunistic omnivores, they prefer food sources that are readily accessible and away from busy human developments. Even food conditioned bears prefer to use the cover of night and forest to enter heavily populated areas.

During the closure of Yosemite Valley, bears spent more time in developed areas in search of natural food sources. In the absence of park visitors, they boldly crossed roads, bike paths, and walked through empty campgrounds, parking lots, and through other areas that are typically swarming with people. Bears took advantage of the historic apple orchards, gorging themselves on apples. The Majestic Yosemite Hotel (formerly The Ahwahnee) lawn, usually filled with visitors picnicking , wedding parties and kids playing was now instead the location two male bears chose to play together, grazing on the grounds.

Bear at the Majestic Yosemite Hotel (Photo: Dakota Snider)

This behavior gives biologists a glimpse into a more wild Yosemite Valley when it was only sparsely populated and much less visited. A time when black bears and other wildlife were able to chose the path of least resistance, instead of the path of least population to obtain natural food sources such as fruits, insects, acorns, and grasses.

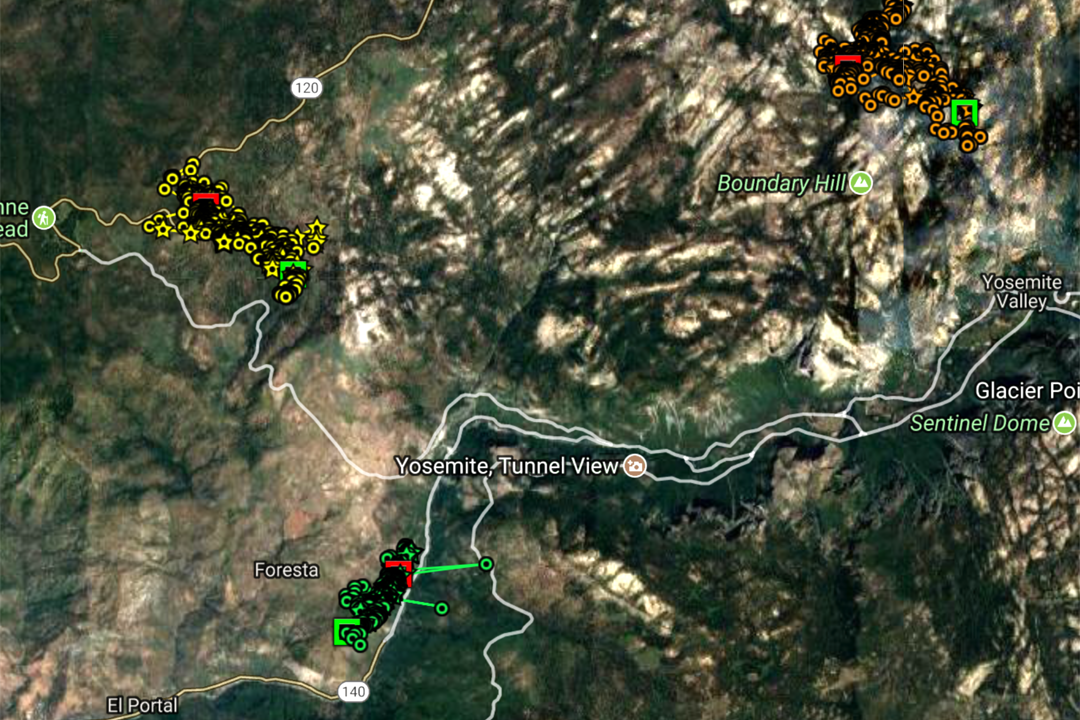

GPS tracks showing bears in Yosemite Valley during the Ferguson Fire

Hungry Fall Bears – Residents Beware!

During fall, in preparation for hibernation, bears eat up to 20,000 calories every day. That’s like eating nine large cheese pizzas, about 35 medium bean and cheese burritos, or 93 Snickers bars every single day! In terms of a bear’s natural diet, that’s equal to over 11 pounds of acorns or around 100 pounds of berries.

Bears looking for food, particularly this time of year, can be attracted to residential areas by many natural food sources (acorns, fruit, wasp nests) and if residents’ food and/or attractants are not properly stored, they’ll take advantage of that, too. Bears exposed to human food, or just used to being in residential areas, can quickly become food conditioned (meaning they’ve learned to associate people or development with food), or habituated (in which they lose their natural fear of people, often getting dangerously close to people or homes). They may even start entering homes for food, which can quickly become dangerous for residents and bears alike. Simple things like keeping windows and doors closed and latched, properly disposing of trash and recycling, not using bird feeders (these also are great bear feeders), and cleaning barbeque grills each time you use it, can do a long way in protecting bears if you live in bear habitat.

In October, one thing many people don’t consider when living in (or visiting) bear habitat, is that pumpkins are not only one of our favorite Halloween decorations, but they are also food. In Yosemite we’ve seen bears eat pumpkins in neighborhoods numerous times, and so we ask that people keep them inside except for during active trick or treating. We also remind residents never to leave candy out on their porches…a treat too tempting for a bear to walk past.

Troublesome Teens – Yearling Bears in Yosemite

Summer is upon us! The days are longer, the weather is warmer, and the kids are finally out of school and ready to explore their new-found freedom; and in a similar capacity, so are the young black bears of Yosemite. The transition from spring to summer is a coming-of-age time in the lives of young yearling black bears, when they are forced to leave their mothers’ sides and begin life on their own. These yearling bears set off on their own in May and June after spending a full year with their mother learning the way of the woods. However, they are still naïve and extremely curious, making this a crucial window for their behavioral development and the focus of many management efforts as they try to find their place in the world during these early summer months.

In their first year of life, black bear cubs learn and grow under the watchful eye of their mother. They learn foraging habits and feed off of the sow’s extremely nutrient-dense and fatty milk, rapidly taking on weight. A year passes before the mother stops providing for her now 40-to-80-pound offspring, and instead chases it off. The sow will do this (often repeatedly) to send a message to her offspring that their free ride is up and it is time for them to be self-reliant. This is mainly triggered by the energy demands of the rapidly growing yearling, which outpaces the sow’s ability to provide for it, along with her own need to put on weight and a budding interest in reproducing again.

In their first year of life, black bear cubs learn and grow under the watchful eye of their mother. They learn foraging habits and feed off of the sow’s extremely nutrient-dense and fatty milk, rapidly taking on weight. A year passes before the mother stops providing for her now 40-to-80-pound offspring, and instead chases it off. The sow will do this (often repeatedly) to send a message to her offspring that their free ride is up and it is time for them to be self-reliant. This is mainly triggered by the energy demands of the rapidly growing yearling, which outpaces the sow’s ability to provide for it, along with her own need to put on weight and a budding interest in reproducing again.

These yearling bears are well prepared for life and capable of beginning on their own. However, they’ll need to establish their own home range and find their own food sources without the helpful guidance and added security they previously had with their mother. It takes a bit of time and a lot of and exploring from an already innately curious creature, which can get them into trouble if they find themselves in campgrounds or around other human populated areas.

The majority of bear reports in Yosemite in the last month have been from yearling bears in and around campgrounds. What seems like an innocent pass-through of these campgrounds (or any other human populated area for that matter) can be detrimental to their development if met with a human food reward or increased comfort around people. While these yearlings venture out for new territory and food sources, they are constantly learning and picking up habits (both good and bad) that will stick with them for life, making them extremely vulnerable to becoming habituated and food conditioned. If a bear gets human food in a campground, from a backpack, a cooler, or even overflowing trash, it creates a nearly irreversible learned behavior for that bear to associate these objects and areas as potential food sources. At that point, a bear might alter its normal foraging behavior and spend some of its time opportunistically searching for human food, beginning a downward spiral in behavior.

Many of our management efforts are aimed at preventing these bears from ever getting to the point of becoming habituated and/or food conditioned due to human negligence, but it is not always enough. With the amount of visitation Yosemite receives, the margin for human error is small, so each year bears obtain human food and become habituated and/or food conditioned. At that point, our next response is a tireless effort of extensive monitoring and negative conditioning routine of these bears whenever they exhibit these behaviors, in hopes of returning these bears to their wild ways. Patrols can turn into all-night affairs in an attempt to remove human food from their diet. The quicker we can intervene the better, which is why it’s critical to report all bear sightings to the Yosemite Bear Hotline at 209/372-0322.

Many of our management efforts are aimed at preventing these bears from ever getting to the point of becoming habituated and/or food conditioned due to human negligence, but it is not always enough. With the amount of visitation Yosemite receives, the margin for human error is small, so each year bears obtain human food and become habituated and/or food conditioned. At that point, our next response is a tireless effort of extensive monitoring and negative conditioning routine of these bears whenever they exhibit these behaviors, in hopes of returning these bears to their wild ways. Patrols can turn into all-night affairs in an attempt to remove human food from their diet. The quicker we can intervene the better, which is why it’s critical to report all bear sightings to the Yosemite Bear Hotline at 209/372-0322.

It’s hard to express just how heartbreaking it is to see a wild Yosemite bear, especially so early on in its life, begin down a path to habituation and food conditioning. What was once a wild and self-reliant bear becomes a sad symbol of the mark we as man have on nature. However, through proper food storage, keeping our distance, educating people, and respecting wild animals can we lessen the impact we are having on Yosemite bears and continue to coexist with these charismatic creatures.

Bears and the Bees

Bears seen right before mating occurred (Photo: Andi Stewart)

Spring is transitioning into summer and mating season in Yosemite has begun! Bears are solitary creatures and aren’t often seen in pairs or sloths (a group of bears is called a sloth). However, there are a few common exceptions: when food is overly abundant in one specific place, when sows have cubs or yearlings, and in the late spring and early summer during mating season (May–July).

Bears generally become reproductively mature between the ages of 3 and 5 years old. Bears are polygamous, so it is common for an individual bear (of either sex) to mate with multiple bears within one mating season. A female bear may give birth to cubs with different fathers in the same litter. Male bears will court females with a variety of behaviors, including barking, biting, hugging, mock fighting, and kissing. This behavior can take between a couple hours up to a couple days.

Even though bears mate and eggs are fertilized in the spring/summer, embryonic growth will not occur until fall. This is because bears use a clever reproductive strategy called delayed implantation. This allows for bears to only have the number of cubs that their bodies are able to support over the winter. if they have a lot of fat stored in the fall, they are likely to have more cubs than if they are thin. On average, a bear will have a litter of two cubs, but a very well fed bear could have three or more! Likewise, a thin bear may only have one cub, or none that year. Cubs are born between January and February weighing less than a pound.

Females mate and have cubs every other year. Their cubs stay with them through their second spring, when it is time for the sow to mate again. This is when the one-year-old bears (yearlings) will go off on their own. These yearlings are often mistaken for cubs who are missing their mother. They are generally between 50 and 80 pounds and are trying to find their place in the landscape. Female yearlings are less likely to disperse than males, often having overlapping home ranges with their mother even into adulthood.

It is very important to always keep a safe distance from all wildlife in Yosemite National Park (a minimum of 50 yards from any bear). Mating bears can exhibit unusual behaviors and males may become more aggressive. Females with cubs can be protective of their young, and yearlings out on their own for the first time have a particularly hard time staying out of trouble with humans. It is crucial that they keep their natural fear of humans, and never learn about human food, so that they can remain wild. This is an exciting time to see bears exhibiting wild behaviors, but please, for your safety and theirs, always protect your food from wildlife and never approach wild animals, even if it means giving up on that perfect photo opportunity.

Bears Like Trails Too!

Trails make getting through the rugged Yosemite wilderness easier for bears and humans alike. This GPS track shows an adult male bear that decided to follow a few of the scenic trails leading out of Yosemite Valley one day in the summer of 2014. Yosemite’s trails traverse much of the park, and humans and bears often agree on the best trailside rest stops, access to water, and cozy campsites. Unfortunately, this also means that bears can learn to associate busy trails with opportunities to find dropped food, unattended packs, and even beg for handouts. While it’s not necessarily common to stumble upon a bear while hiking, there are a few things people can do to help wildlife.

Wild bears naturally avoid human activity, but as a they spend time in the presence of people without experiencing negative consequences they may quickly become habituated. When bears become habituated to human presence, they lose their natural instinct to fear or avoid people and are more likely to spend time along popular trails. As bears learn to move comfortably in busy human environments, their opportunistic nature inevitably leads to conflict. A bear that spends significant time around people is much more likely to find an unattended backpack, open bear canister, or food trash. The first time a bear obtains high-calorie human food, it can quickly become food conditioned and preferentially seek out areas of human activity in search of it. This behavior often results in escalating conflicts where wildlife managers are forced to intervene; oftentimes on crowded trails or in remote wilderness locations.

With the privilege of hiking in the stunning Sierra Nevada mountains comes the importance of learning trail etiquette, including appropriate behavior around black bears. Day hikers and backpackers in Yosemite have the responsibility to stay within arm’s reach of their food while hiking by never leaving their backpack unattended or walking away from their food while picnicking. Anyone staying overnight in the park’s wilderness needs to carry an allowed bear-resistant food container to keep bears and other wildlife from accesing its contents (and so that a backpacker won’t lose all their food to a bear). It is important to give wildlife space (at least 50 yards for a bear), even if that means waiting for a bear to move off a trail before proceeding. Surrounding a bear on a trail may force the animal into close proximity to humans, block its escape routes, and/or create a dangerous situation for both people and the bear. If you encounter a bear on the trail, give the animal plenty of space and protect your food. Keep it with you. Do not abandon it, or throw it to the bear as a distraction. If the bear approaches you, a campsite, or is attempting to eat human food, gather together and yell, “Get out of here, bear!” as loudly as possible. Report all bear sightings to Yosemite’s Bear Hotline at 209-372-0322.

Although particular bears may seek out easy high-calorie human food, natural food sources are plentiful for the well-adapted American black bear. They do not need our food to survive, rather the opposite. They need to avoid our food in order to maintain their natural bear behaviors, and avoid conflict with people. Grasses, insects, berries, and acorns provide ample food for bears in wilderness. Remember, the ONLY help they need from us is respect and distance!

An Unknown Future – Orphaned Cubs (Part 3)

Orphaned cubs emerging from their den (Photo: NPS)

[Read parts one and two of this story.]

Leaving the yearlings at the den site was hard; after all the effort everyone had put in to get them to that point. Biologists watched their GPS data closely, and after about a month of hibernation in their human-made den, the bears began to explore their surroundings. Trail camera photos showed them playing with each other as they explored their new home, with the larger male expressing dominance and playfully chasing the others around their den site. After another month, the three intrepid young bears began to disperse, venturing to find their own home ranges and stake a claim in Yosemite’s expansive wilderness.

GPS data showing yearling dispersal in July 2017 (Credit: NPS)

The smaller of two males settled in an area between Foresta and the El Portal Road, high on a ridge. He kept to himself, and moved around a lot, likely searching for various food sources, but he never interacted with people on trails or in developed areas. This bear’s collar stopped communicating GPS points to satellites in late spring. Without location data from the collar, biologists could now only track this bear using radio telemetry (which is limited by geography and distance: to pick up the collar’s signal via radio waves, biologists must be within ‘line of sight’ of the collar, and close enough to hear it using a radio receiver). It took the rest of the fall and summer before the collar was found, which required dedicated biologists bushwhacking several hours through manzanita on rough terrain. Unfortunately, when they found the collar, they also discovered remnants of fur and the bear’s ear tag which led them to believe the bear had died earlier in the year from natural causes. While the collar failed to transmit GPS locations after late April, data recovered from the collar indicates that this bear died in late June 2017. This bear was too far from development to assume that the death was related to humans, and it is common for wild animals to die naturally within their first few years of life (generally, about a quarter of black bear cubs are expected to die during their first year, and a third die within the next two years).

The small female sibling settled in an area near Yosemite Creek, deep in the wilderness. Her collar transmitted until the day it automatically dropped off in July. Our last glimpse of her was along a trail, far from roads and people; she looked healthy and acted skittish around humans. She may end up living 30 years or more in Yosemite’s wilderness, raising cubs of her own, foraging on wild berries and insect larvae, existing as an integral part of the glorious wildness she was born into.

The third cub, the larger male, had a more elaborate (and cautionary) story. For quite a while, this bear found good natural forage around a closed seasonal campground in the park. However, once the campground opened to visitors in June, the bear began foraging opportunistically in the same area on human food and garbage that was either left out or improperly stored. Very quickly, staff from across the park pulled together and began an around the clock effort to protect this tenacious little bear, including continuous education of campers, increased trash pick-ups, and long nights of chasing the bear out of the campground in hopes of convincing him that people were scary, and not worth the opportunistic food rewards. However, when all of these efforts were clearly not working to change the bear’s behavior, biologists decided to try relocating the bear. While bear relocations are generally unsuccessful, they sometimes work on young animals that are still establishing home ranges. So, this bear was relocated a short distance away in suitable habitat, where he immediately went back to foraging naturally and avoiding people.

Orphaned yearling foraging on wild grapes (Photo: Drew Wharton)

A bear’s life, however; revolves around a continuous search for food; and since food availability changes seasonally at different elevations, bears must move to follow that available food. Heading into fall, wildlife management staff began receiving reports of this bear seen passing through a residential area over 15 miles (as the crow flies) and roughly 4,000 feet lower in elevation from where he spent his summer. By November, this bear had dropped down into the park’s administrative site, El Portal. There, the bear was gorging on natural food, including wild grapes and acorns. The only problem was that all this great natural food was, again, close to people; in a residential area and next to a busy highway. Bears that become comfortable close to people around homes worry wildlife managers, because it only takes one human mistake, like leaving a window open or garbage out, for a bear to get a large amount of food and associate this reward with people and houses. If that happens, it can immediately and dramatically alter the bear’s behavior as it shifts to actively seeking out human food or breaking into buildings instead of continuing to forage naturally. Knowing this, wildlife management staff again dedicated their time to scaring the bear out of developed areas and increased efforts to alert the community to be vigilant about food storage.

Days passed with community members and park staff pulling together in hopes of keeping this bear safe until the season turned and winter arrived, when food would become scare and this bear would hopefully find a den for the winter away from the neighborhood. Unfortunately this time, all of the hard work and joint efforts to give this bear a long, wild life eventually failed. On October 30, wildlife management staff found this bear, orphaned after its mother was hit and killed by a car, also dead in the road. It was a somber day. We all know that speeding kills bears—or more accurately, driving kills bears–—but it was hard to stomach that this would be the fate of a bear who we thought we saved from the same tragedy two years earlier.

‘Red Bear Dead Bear’ sign at location of vehicle-bear collision (Photo: Drew Wharton)

This project, along with the data we have collected over years of careful monitoring of bear vs. vehicle collisions in Yosemite, has hit home with resource managers and many others in Yosemite. All it takes is having to drag one dead bear off of the road in order to realize how impactful our driving can be to other species. Wildlife-vehicle collisions are one of the largest human-wildlife conflicts we face today, and we all need to do more to change these statistics. This is an issue the National Park Service has worked hard on with limited successes in past years. With as many as 39 reported bears hit by vehicles in the park in a single year, we are dedicated to use this new momentum to refocus our energy on creating new partnerships, new tactics, and new solutions for this difficult problem.

An Unknown Future – Orphaned Cubs (Part 2)

In January 2017, the sibling yearlings—orphaned after their mother was hit and killed by a car on Independence Day, 2016—had been in hibernation for more than a month already. The cubs, once weighing eight pounds each, now weighed between 63 and 95 pounds, after being well nourished through their first year by the Lake Tahoe Wildlife Care Center (LTWC). They were healthy, fat, and ready to be transferred back to the park to a pre-selected den site that biologists prepared in Yosemite’s wilderness for this purpose.

In preparation for their return to Yosemite, park biologists went to LTWC to assess the yearlings’ body condition and health, and to fit them with GPS collars, which were funded by donations to Yosemite Conservancy. The collars would allow park staff to monitor how long the bears stayed in the den and to watch the movements of the cubs once they left the den in search of food. The collars were programmed to automatically drop off after six months, before the cubs outgrew them, and the information collected by these GPS collars would allow biologists to better understand the bears’ behaviors and how successful they were as wild, independent bears.

As the park biologists made the long drive back to Yosemite with bears in tow, a group of thirty park employees and volunteers made preparations to ski the bears on sleds to the den site. This included retrofitting rescue sleds with bear traps, harnesses for people to pull and push the bear traps, and preparing hot water bottles and lining the traps with hay to keep the sedated bears warm on their trip. With everything assembled, three teams began transporting the precious cargo up the mountain while one biologist skied alongside each sled to monitor the bear’s condition during the journey.

It took several hours and a lot of work, but all three bears arrived at the designated site. In the winter of 2016 to 2017, California broke its five-year drought with impressive amounts of snowfall. This allowed for great skiing and promising conditions for the yearlings to remain in the den. It also meant that the den site, which was located at the base of a tree, was now under six to 10 feet of snow. Staff excavated a hole to get down to the opening. Each bear was carefully lowered into the den with hopes they would remain there, sleeping the rest of the winter.

The yearlings had made it back to Yosemite, and back into the wild after seven months. The bears had been given the best chance possible, and now their fate was their own once again. They were returning to what we hoped would be a wild and free existence. Everyone present took a moment to appreciate the magnitude of effort it took to get these bears through their first year, and to say goodbye to these bears that we would hopefully never see again as they lived their lives, far from people as wild bears.

To be continued in next month’s blog.

An Unknown Future – Orphaned Cubs (Part 1)

It was Independence Day weekend 2016, and Yosemite was bustling with people hiking, camping, and taking in the scenery. For most visitors, Independence Day is a welcome break, a long weekend in the middle of summer. For park staff, it’s the busiest time of year, and employees across the park work hard at their jobs through the holiday providing visitor services and protecting the park. That morning, the wildlife management staff got one of those calls they dread the most: a bear was hit and killed by a car while crossing Tioga Road.

Between 1995 and 2017, an average of 18 bears have been reported hit by vehicles each year in Yosemite. Of those, 27 percent are found dead or are euthanized after park rangers determine the bear has an incapacitating injury. Bears that aren’t incapacitated by their injuries typically flee and their fates remain unknown. Some are OK, some sustain an injury that will give them a lifelong limp, and others ultimately die as a result of their injuries. Most bears are hit by cars from June through September, which coincides with Yosemite’s busiest months for visitors and the time during which bears are most active.

Ultimately, the human-bear management story in Yosemite is a metaphor for all the ways people and bears overlap in this beautiful place. Bear-vehicle collisions are possibly the most visual, most literal, and most heartbreaking example. While being called to a bear hit by a vehicle is unfortunately common, this particular incident was anything but routine. When rangers arrived on scene, they discovered that the dead bear was a lactating female and that there had been possible sightings of three cubs in the area. This news forced biologists to drop everything else to focus on these three orphaned cubs.

Cubs are generally not successful surviving in the wild in their first year without their mothers. Young bears spend their first 16 or so months with their mother learning how to forage, keep away from predators, hibernate in the fall and winter, and a whole host of other life skills. So even though young bears may not need the nourishment from their mother’s milk, they need her life experience and knowledge to survive. Consequently, leaving these cubs alone would almost certainly ensure their deaths.

With the hopes of getting these young bears through their first year, biologists and park staff mobilized quickly to find and capture the cubs while simultaneously seeking placement for the cubs at the Lake Tahoe Wildlife Care Center.

Biologists set out small metal cub traps and were fortunate to capture all three cubs within an hour of each other (similar captures in the past have taken more than 24 hours!). Shortly thereafter, biologists transported the cubs to the wildlife care facility. The cubs remained at the facility through the remainder of the summer, fall, and part of the winter. The goal of the rehabilitation was to fatten them up enough to give them the best chance at surviving on their own the following year with as little human interaction as possible so they would retain their natural fear of people when reintroduced to the park the following winter.

(Part two of this blog will be available on March 5)