Bear Awakening

(Photo: J. Hadley)

Bears are up and moving in Yosemite National Park! They have been spotted moving around from the Sierra Nevada foothills to Tuolumne Meadows in the high Sierra. Bears typically emerge from hibernation in March or April in Yosemite depending on food availability, elevation, and weather. Adult male bears awaken first, followed by solo females and juveniles, and finally sows with cubs. In mid-May, the first spring cubs were spotted in the park on the Yosemite Falls Trail.

The newly awakened bears are hungry! Bears in Yosemite Valley eat new grasses, flower buds, and fresh roots in the early spring along with leftover natural food (especially black oak acorns this year) from the previous fall. Bears also use meadows and vernal pools to consume new sedges high in sugar. As spring progressed, bears were observed tearing into decaying logs looking for insects and nests. In June, bears began eating fruit including white stemmed raspberries and non-native apples. Despite the fresh growth available as food, Yosemite bears can continue to lose weight into May while their metabolisms recover from hibernation.

Besides working on regaining weight lost in hibernation, multiple male bears were observed following female bears around starting in early May. This seems early as the courtship of sows by boars (mating season) usually does not begin in the Sierra until early June. Sows will aggressively chase off their yearlings this time of year before coming into estrus and mating. The only female bear seen with a yearling in Yosemite Valley was last observed together prior to separating in the first week of May. While black bears mate in late spring or early summer, the fertilized egg does not implant until fall to make sure the female’s body condition can support a pregnancy to term.

How can you help protect these bears this summer? The same things we need to do every day to keep bears alive and wild! Store food and trash (anything with a scent or calories) within arm’s reach of an awake person or secured in a building, bear canister, or food locker. Stay a minimum of 50 yards away from bears and further if your presence is changing their behavior.

Yosemite Bear Facts — July 6th, 2025

2025 Total Property Damage: $3,937

Bear Incident Comparisons (year to date—previous years compared to 2025):

· Fewest Incidents (2019) – up by 170%

Bear Activity Summary: Bears are active throughout the park. Bears are shifting from eating early season sedges, grasses, and grubs to soft mast including berries and other fruiting plants. Mating season appears to have ended at lower elevations. June was a busy month for bears in Yosemite Valley with ten reported incidents of bears obtaining unsecured human food. Most of these occurred in Curry Village, where guests did not properly close and latch their bear-resistant food storage lockers. There were several additional incidents of a bear obtaining human food in White Wolf Campground. Keeping food in hand or locked away is the best way to protect bears in Yosemite National Park. In campgrounds and tent cabin areas, this means keeping food locked inside a closed and latched locker when not in use. Bears that obtain human food can become dangerous or aggressive and may be killed to protect public safety.

The first confirmed vehicle break-in by a bear occurred this month in Yosemite Valley, causing $2,460 in property damage. Visitors, residents, and employees are reminded that it is illegal to keep food store inside a vehicle overnight in Yosemite. Food to a bear is any item with a scent or that contains calories. During the day, all food in vehicles must be stored out of sight. Please remember to roll your car windows all the way up and lock your car doors. Never leave food/ice chests outside your vehicle ( i.e. truck beds or strapped to a carrier). The lives of Yosemite bears depend on it!

Red Bear, Dead Bear: Please help protect wildlife by obeying speed limits and being prepared to stop for animals in roadways. Nine bears have been struck in Yosemite so far this year, including six in the month of June alone.

Fascinating Bear Facts: While only black bears live in Yosemite today, historically both black and brown bears were found in the Sierra Nevada. Where both species coexist they typically live in lower population densities than in the same ecosystem type where black bears live alone.

Other Wildlife: Coyotes have been active in Yosemite Valley. Please be sure to leash pets at all times to keep wildlife and your dog safe! It is the law!

Please report bear incidents and sightings: Call the Save-A-Bear Hotline at 209-372-0322 or e-mail yose_bear_mgmt@nps.gov.

Yosemite Bear Facts – March 30, 2025

2025 Total Property Damage: $704

Bear Incident Comparisons (year to date—previous years compared to 2025):

-

Last year (2024) – There were no incidents yet last year at this time.

-

Most Incidents (1998) – down by 60%

-

Fewest Incidents (2019) – up by 700%

Bear Activity Summary: Bears are being reported consistently in Yosemite Valley, but are likely active throughout much of the park’s lower elevations. This week bears got food from an unlatched food locker in Curry Village and trash from a residential garage. So far this year bears have been documented getting into human food and trash in most lodging and camping areas, as well as in many residential areas.

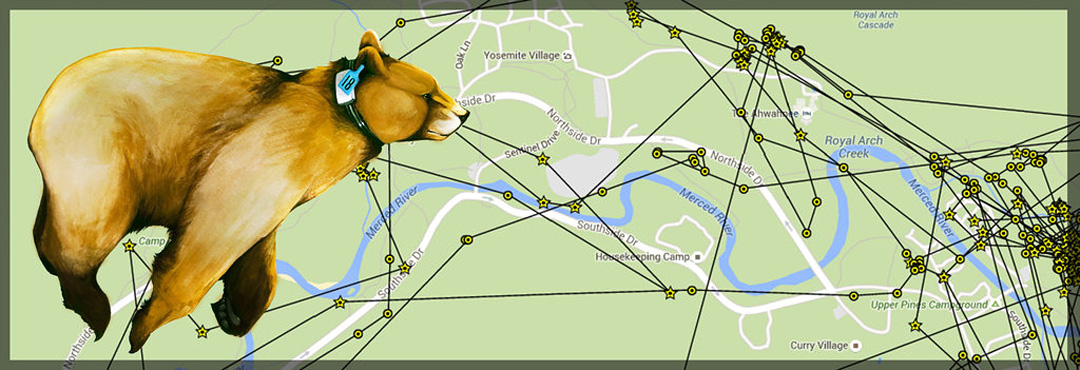

Last week, wildlife management staff captured and GPS collared an adult male bear suspected of getting into a garage so its behavior could be monitored. Bear jams are occurring almost daily and several sow and yearling pairs have been observed and have caused small crowds in Yosemite Valley. No cubs have been seen yet, but yearlings and adult bears appear to be in good body condition coming from hibernation. Acorns, especially black oak, are still abundant on the ground in the Valley from last fall. Please remember that if you see a bear in the park give it plenty of space (at least 50 yards, but if the bear is reacting to you, you are too close). If you see a bear in a campground, hotel, or other human developed area yell and make lots of noise to scare it away.

Red Bear, Dead Bear: Please help protect wildlife by obeying speed limits and being prepared to stop for animals in roadways. Twenty-one bears were hit by vehicles in 2024 with three confirmed dead. No bears have been documented as hit-by-vehicle so far in 2025.

Fascinating Bear Facts: Black bears have an average of two cubs at a time. Litters of one or three are not uncommon and bears can even have four or more. The litter size often increases with age and body size/condition of the mother. Females generally become sexually mature at three to four years of age, but may be delayed to as late as seven in less productive habitats.

Other Wildlife: Avian influenza is still being reported and monitored throughout the United States. This virus can impact animals beyond birds, including mammals. Remember to not handle or approach any wildlife in Yosemite and report sick and dead animals to Wildlife Management.

Please report bear incidents and sightings: Call the Save-A-Bear Hotline at 209-372-0322 or e-mail yose_bear_mgmt@nps.gov.

Yosemite Bear Facts – March 1, 2025

2025 Total Property Damage: $394

Bear Incident Comparisons (year to date—previous years compared to 2025):

-

Last year (2024) up by six incidents—there were no incidents at this time last year.

-

Most Incidents (1998) – up by six incidents—there were no incidents at this time in 1998

-

Fewest Incidents (2019) – up by five incidents.

Red Bear, Dead Bear: Please help protect wildlife by obeying speed limits and being prepared to stop for animals in roadways. Twenty-one bears were hit by vehicles in 2024 with three confirmed dead.

Fascinating Bear Facts: “Research shows that with every 1°C (1.8°F) increase in regional winter temperatures, (black bears) stay awake an additional six days on average”.—Johnson, Heather; Lewis, David. Human Development and Climate Affect Hibernation in a Large Carnivore with Implications for Human-Carnivore Conflicts. Warming temperatures in the Spring trigger bears to emerge from hibernation and start seeking food again.

Other Wildlife: There has been an uptick in coyote observations in and around roads and development in recent weeks. Roadside coyotes on Big Oak Flat road have been seen and hazed by Law Enforcement staff on multiple occasions. Valley coyotes are also roaming roadways for handouts.

Please report bear incidents and sightings: Call the Save-A-Bear Hotline at 209-372-0322 or e-mail yose_bear_mgmt@nps.gov.

Yosemite Bear Facts — October 20, 2024

Bear Incident Comparisons (year to date—previous years compared to 2024):

-

Last year (2023) – up by 6%

-

Most Incidents (1998) – down by 98%

-

Fewest Incidents (2019) – up by 55%

Bears this time of year are spending the majority of their time eating, trying to pack on pounds for hibernation. Acorns are a primary food source for bears in the fall, and the crop of acorns is particularly large this year. Bear activity has been picking back up in Yosemite Valley the past couple of weeks, with a bear getting into a food storage locker that was not properly latched this week.

Red Bear, Dead Bear: Please help protect wildlife by obeying speed limits and being prepared to stop for animals in roadways. Twenty bears have been hit by vehicles with three confirmed dead.

Fascinating Bear Facts: Fat is the only source of metabolic energy during black bear hibernation. In the fall, bears focus on food with high fat content (such as acorns) over high protein content. Hyperphagia is over-eating in order to build these fat reserves.

Other Wildlife: Mule deer bachelor groups have been very active roadside in developed areas, foraging for oak leaves and acorns causing frequent traffic jams and crowds. Always avoid getting close to wildlife. Deer are particularly unpredictable in the fall with hormonal changes impacting behavior.

Please report bear incidents and sightings: Call the Save-A-Bear Hotline at 209-372-0322 or e-mail yose_bear_mgmt@nps.gov.

Yosemite Bear Facts — July 21, 2024

Bear Incident Comparisons (year to date—previous years compared to 2024):

Bear Activity Summary: Bears have obtained unattended food from visitors and residents in Yosemite Valley and El Portal on multiple occasions. Tent cabins, picnic areas, and residential houses have all been targets of bears opportunistically finding food not properly stored. In Yosemite Valley, two tagged male bears have been actively seeking human food at picnic areas and tent cabin sites. As the raspberries dwindle, apples are becoming the main draw for bears in Yosemite Valley. Untagged bears have been observed foraging on apples and leftover raspberries, sometimes in close proximity to people. In El Portal, a female bear continues to approach and find food in and around unsecured residences. Fruiting trees in El Portal are also a current draw for bears to spend time too close to people and homes—please pick your fruit!

In early July, a human-bear encounter resulted in a minor injury to a hiker who inadvertently collided with a bear on Happy Isles Rd. The tagged bear had just obtained garbage from Upper Pines and ran into hiker walking down the road without a light.

Red Bear, Dead Bear: Please help protect wildlife by obeying speed limits and being prepared to stop for animals in roadways. Eleven bears have been hit by vehicles with two confirmed dead. One cub was taken to a wildlife rehabilitation center last week, it is likely the mother was hit by a vehicle.

Fascinating Bear Facts: Bears can travel great distances to return to a known food source. Relocated bears frequently return within days in Yosemite, and in the process of returning, risk encountering vehicles as well as human development. For this reason, YNP usually avoids relocating bears.

Other Wildlife: Summer is here! The Northern Pacific rattlesnake is a venomous species found in Yosemite. These snakes have excellent camouflage and are easy to miss when hiking hot, dusty trails, or scrambling through talus fields. Always check under objects and rocks when sitting to snack, and if you encounter a rattlesnake, give it plenty of room. Do not try to move the animal, it will move off trail on its own if given space.

Please report bear incidents and sightings:

Yosemite Bear Facts — July 06, 2024

Bear Activity Summary: At least two different bears have been very active in the northern Yosemite Wilderness, spending much time near the Vernon Lake campsites. Bears have been approaching campers and obtaining improperly stored food. Staff from multiple divisions have been doing targeted patrols in an effort to scare these bears away from people to prevent further incidents. Backcountry users are being reminded about the importance of proper wilderness food storage, and how to act quickly to scare a bear from a human occupied area by yelling and not abandoning food. A sow with two cubs has been active near the JMT and Mist trails.

Red Bear, Dead Bear: Please help protect wildlife by obeying speed limits and being prepared to stop for animals in roadways. Seven bears have been hit by vehicles with one confirmed dead.

Fascinating Bear Facts: Bears can travel great distances to return to a known food source. Relocated bears frequently return within days in Yosemite, and in the process of returning, risk encountering vehicles as well as human development. For this reason, YNP usually avoids relocating bears.

Other Wildlife: Summer is here! The Northern Pacific rattlesnake is a venomous species found in Yosemite. These snakes have excellent camouflage and are easy to miss when hiking hot, dusty trails, or scrambling through talus fields. Always check under objects and rocks when sitting to snack, and if you encounter a rattlesnake, give it plenty of room. Do not try to move the animal, it will move off trail on its own if given space.

Please report bear incidents and sightings: Call the Save-A-Bear Hotline at 209-372-0322 or e-mail yose_bear_mgmt@nps.gov.

Yosemite Bear Facts — April 27, 2024

2024 Total Bear Incidents: 0

2024 Total Property Damage: $0

Bear Incident Comparisons (year to date—previous years compared to 2024):

Fewest Incidents (2019) – down by 100%

Bear Activity Summary: Four male bears have been active in Yosemite Valley. Green 23, Yellow 20, and White 42 are GPS collared bears who have been causing bear jams in the Valley due to roadside forage. These bears are primarily grubbing in downed logs and grazing on shoots and grasses. Another untagged large male black-colored bear has been seen along riverbanks in the Valley frequently. Purple 1, a female bear who spends time in El Portal, has been active for over a month both in and out of town. Two other GPS collared females are still in or very near their winter den sites.

As bears emerge from hibernation, they will take advantage of any food they find. Cubs of the year and yearlings are especially vulnerable to learning negative behaviors as they encounter humans and human food sources. It is extremely important to keep unoccupied buildings secured (all windows and doors latched or locked), keep all food stored in bear lockers when camping, keep your vehicles clean of all food, drinks, and other attractants like toiletries or gum, only use bear proof dumpsters and trash cans to throw away your food waste, and keep your backpacks and food with you (within arm’s-reach) while out enjoying the park.

Red Bear, Dead Bear: Please help protect wildlife by obeying speed limits and being prepared to stop for animals in roadways. One yearling female was hit and killed by a car this past week. A gray fox was also hit and killed by a vehicle on the Big Oak Falt road near Foresta.

Fascinating Bear Facts: Bears break logs apart while searching for grubs (larvae of wood-boring beetles). This process not only feeds the bear, but supports the decomposition process and soil re-nutrition cycle.

Other Wildlife: Spring is here! Help protect baby wildlife by leashing pets and by keeping your distance. Please leave baby animals where you see them. Deer leave their fawns to go forage and return to them throughout the day. Fledgling birds may be on the ground under a nest as they learn how to fly. These behaviors are normal, and humans trying to help usually cause more harm than good.

Please report bear incidents and sightings:

Bear Ahead!

Photo Credit: Drew Wharton

Photo Credit: Drew Wharton

Photo Credit: Drew Wharton

For bears, their natural fear of people is an important instinct that keeps them safe. When a bear becomes habituated, losing its natural fear of people, other behaviors can change and dangerous situations can evolve with people. This is why rangers staffed these areas from late August through November. Rangers also created a fun new display to show people exactly how far they should be from a bear: a fun wooden bear silhouette designed to stand a 50 yards down a trail from a sign with bear information on it. This sign explained what to do if you see a bear, and demonstrated exactly how far visitors should remain from bears in order to help keep them wild. All these efforts, as well as the interest that visitors took to learn and understand their role in protecting wildlife in national parks, helped make a difference in these acorn eating bear’s lives.

HEY BEAR, HI BEAR, GO BEAR!! How and when to scare away a bear in Yosemite.

Here’s the situation: you are hanging out at your campsite or on a picnic area beach in Yosemite, when you hear a branch crack behind you. You turn around to find a bear approaching. What do you do?

You stand up, face the bear, wave your arms, and yell at the bear. We mean YELL at the bear, as loudly as you possibly can. Be aggressive with your voice and body language. You’re not just making noise; you’re scaring a bear away! You have to mean it for it to work.

Here are some examples of things you can yell:

HEY BEAR!!

GO BEAR!!!

GET OUT OF HERE BEAR!!

Or even just: AHHHHHHHHHHHHHH BEAR!!!!!!!!!

One half-hearted yell may not be enough to scare a bear. So, keep yelling LOUDLY and AGGRESSIVELY until the bear leaves. Yell, clap your hands, wave your arms, hit a stick against a tree, get other people to help you yell! You can even throw small objects like pinecones or small pebbles at the bear to help scare it. (You’re trying to gently hit the bear with the pebble or pinecone—not injure it: Bears don’t like being touched.) Don’t chase the bear; just use your voice to scare it away.

Do you have time to snap a quick picture? No!

Do you have time to look around for a pot to bang or a whistle to blow? No! Use your voice! Your voice is your most effective tool to scare a bear away (and you don’t have to go looking for it… unless you’re really scared).

When a bear is around people, it could be only moments away from getting food, so you need to make it feel unwelcome immediately. Once a bear is eating food, it will be harder to scare away and much more likely to return in search of more food, ultimately getting itself into more trouble. We also want bears to be immediately afraid of people (as they naturally are), rather than assuming most people aren’t scary.

Bears that consume human food typically have decayed and damaged teeth. But that’s not the only negative consequence: when a bear gets food from people, even just a banana, the bear will change its natural behavior. Bears are extremely food-driven and a bear that gets human food will often become so bold in its attempts at getting human food that it has to be killed to protect people. So, when you see a bear approaching you or in any developed area (e.g., campground, picnic area, trail, parking lot), it is important to scare it away immediately, stopping this cycle, and helping keep the bear wild and alive. Yes, yelling at a bear helps keep it alive.

What about when you see a bear in a meadow, in the wilderness, or anywhere else away from human development or people—should you scare it? Generally, no. Do you have time to snap a quick picture? Probably, if you are at least 50 yards away from the bear. It can be one of the best Yosemite experiences getting to watch a wild bear do wild bear things.

Are you having trouble envisioning scaring a bear away? This video shows what it sounds and looks like. This advice applies in Yosemite; always check local recommendations when visiting bear country.