Where Do Bears Go in Winter?

It’s January, but Yosemite has only seen a small amount of snow. So where are the bears? Are they hibernating yet? The answer might be more complex than you’d expect. Hibernation in black bears is dependent on food availability – meaning that once a bear is using more energy than they can find, they’ll hibernate. Bears that continue to find enough calories foraging in the late fall and winter may go into hibernation later, or skip it altogether (these bears are more often males). Likewise, if bears have access to human food or trash in the winter, they may skip hibernation altogether, even in winters with heavy snow accumulation. There were several accounts on social media of this occurring last winter in the Tahoe Basin. It’s critical to maintain proper food storage year-round. Making the assumption that all bears are hibernating as soon as the weather cools off is a common mistake that can be much more difficult to correct than maintaining proper storage of human food and garbage year-round.

Most years, the majority of bears in Yosemite begin closing in on a hibernation location starting as early as October. GPS data paired with observations of family groups in the spring have shown that pregnant females are the first to select dens. Bears in Yosemite typically select hollowed out fire cavities in large trees or caves formed by large rocks in talus fields. The majority of the dens we have located here in the Park are very difficult to access with protected entry ways and good vantage points to observe potential threats from the entrance. Once the den location is selected, bears may continue to move around scouring the area for food while continuing to prepare their den. We can see this behavior using their GPS data as they begin to travel much smaller distances, circling back to their chosen den site. GPS data has also shown that bears often move into their dens, even traversing long distances, in advance of the first significant snow storm. Once the availability of fall foods fade, they will enter their den and begin hibernation (typically later in November, and December).

- Den site

- GPS collar found in den

- Bear Team rappelling down after GPS collar retrieval

- Bear tracks showing 4 months of movement prior to hibernation

- Bear tracks showing movement as bear prepares den site

In the late fall and winter months, we remove the BearTracker data to ensure the locations of the bear’s dens are protected. Hibernation is incredibly important for bears and is physiologically astonishing. While hibernating, bears don’t eat, urinate, or defecate. Preparation for a very short gestation drives pregnant sows into dens that will protect them from the elements and predation. Cubs are born in late January and nursed for the first few months of their lives. It’s an important time in a cub’s life since they are born weighing less than a pound and must gain several pounds before venturing out of the den. Once in hibernation, bears in Yosemite typically don’t become active again until late March or April. When they do come out, they’ve lost up to ⅓ of their body weight, and spend their time foraging on early spring foods-usually fresh grasses in meadows. Males are typically the first to emerge for the season while sows with cubs are usually the last to emerge for the year.

So, where are the bears now? Most of them are hibernating, but not all! This is turning out to be one of those late hibernation years for some bears. We have observed several bears continuing to forage on this year’s plentiful Black and Live Oak acorns at lower elevations throughout December. Even females and their cubs were out late, as you can see in the image above of a sow and her cub’s tracks in the snow that was taken in late December.

So Where Are You Taking That Bear?

When visitors see us moving a bear trap in Yosemite National Park, they often ask: “So…where are you taking that bear?” When we discover a black bear obtaining human food and damaging property in Yosemite, we capture it to identify it and usually attach a tracking device. So, why then don’t we simply relocate the bear to a remote area of the park? Indeed, the National Park Service did that for many years. In recent years we’ve all but stopped this practice here. Why? It doesn’t work.

Relocation implies that once moved the animal will stay put. There are several reasons moving bears doesn’t work. The most obvious — they usually return, often very quickly. For that reason we have adopted the term “translocation,” which implies that if you move a bear out of an area there is no guarantee it will stay put. More often than not translocation is nothing more than a temporary fix to a much larger problem.

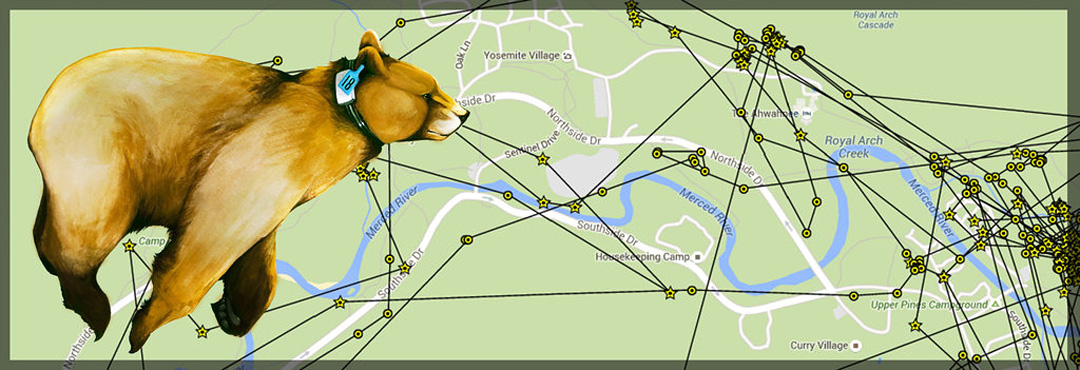

For the first time in Yosemite wildlife biologists have a new tool to remotely track bears — GPS collars. To test the theory that translocation could be an effective management tool, several bears have been moved as far as possible within park the park boundary since 2014. This blog focuses on an individual we moved in 2015. As you can see from the map below, the bear returned to nearly the exact location in Yosemite Valley in less than a week. It’s unclear how bears navigate back home but they do it consistently, as generations of wildlife biologists and park rangers can attest. (The old joke is that the “relocated” bear beats the wildlife management truck back to Yosemite Valley.)

Sometimes bears don’t return home. In these cases it’s usually because they have found easy human food in another location (a nightmare for bear managers located hours away). In other cases bears may get hit by cars while trying to return home or may be chased off by other dominant bears already living in the area they were moved to. These bears could also chase off a less-dominant bear already living in that area. Simply put, moving bears into foreign locations, away from their home ranges and into those of other bears, can cause a negative domino effect.

So what should Yosemite do when a bear starts investigating human food sources? Our focus is to prevent that animal from ever obtaining human food in the first place! The techniques wildlife biologists use to manage black bears are often ineffective as long as bears are able to access human food. It is the crux of human-bear conflict. It’s up to us to store food properly so bears and other animals can’t obtain it. If we all do our part, these animals can retain their natural avoidance of people and have the chance to live a long and wild life. After all, if bears can’t live in national parks, where can they live?

Out of the Campsite and onto the Road: One Bear’s Struggle to Survive Alongside Park Visitors

National parks exist to protect wild and inspirational places, unimpaired, for this and future generations—to create the opportunity for people to experience these regenerative natural places, for the most part, as they would be without the impact of human development. But for wild animals, even our short visits to observe and recreate can have immense effects.

It’s early summer, and calls are flooding into the save-a-bear hotline. “A bird is stuck in our foyer,” “There’s a rattlesnake by my front porch,” and “How do I get a squirrel out of my Sprinter van,” interspersed with the occasional “There’s a bear in the meadow about 20 minutes from here.” With limited resources and staff, we prioritize our responses by how urgent calls seem to be, and when we first heard about this bear, it sounded fairly innocuous—there’s a bear in the meadow about 20 minutes from here in an area marked by meadows overflowing with the young grasses that bears depend on in the spring. It wasn’t until a couple of weeks later that we were told how close the bear had been getting to park visitors. Apparently, he had sauntered within five feet of people multiple times. If this bear was to remain wild, we had to act immediately.

Within a day, a team of wildlife biologists, technicians, and volunteers were heading out on a darting mission for the bear. By five o’clock that night, the bear, an adult male, was located, darted with a sedative, and fitted with a GPS collar: one of our most effective tools in the constant battle to keep Yosemite’s bears safe and wild.

Bears are incredibly intelligent animals, and this one is no exception. He had been spending time closer and closer to human development. Without any negative repercussions, he had been losing his natural fear of humans—becoming “habituated” to human presence. Once bears become habituated, the likelihood of them being involved in conflicts with people skyrockets— which puts us (and the bear) into bad situations. This is why collaring this bear quickly was so vitally important: Once he was collared, we could keep track of his movements (hourly!) and scare him away whenever he came near human development.

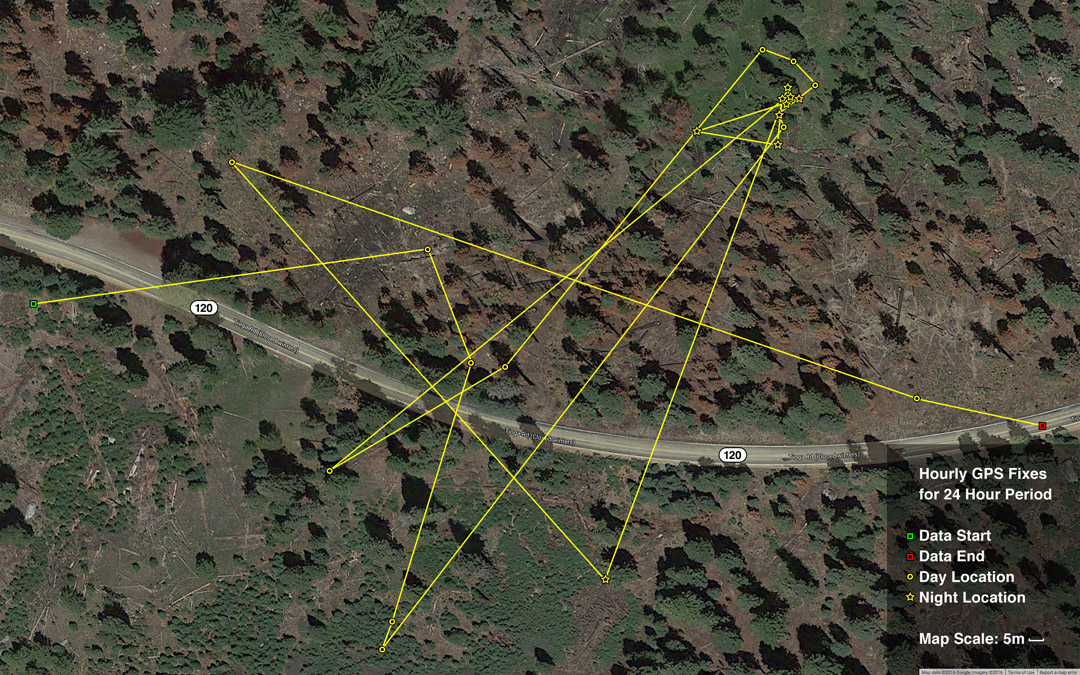

We got to this bear in time. Our intense efforts to reinstill his fear of humans were successful. If he had been fed by visitors, we may not have been so lucky. This bear hasn’t been near campsites or human development at all recently. But for him, it may have been out of the frying pan and into the fire. Today, watching his movements via the data from his GPS collar, we are seeing a surprising trend since he gave up on development: Possibly because of all of the seed-producing trees and grasses that grow in edge ecosystems, he has been spending all of his time on the roadsides of one of the busiest roadways in the park.

Somehow, this bear has crossed this major road hundreds of times since his capture in June. With 27 bears hit by vehicles in the park last year, this realization shocked us, and I think we are all holding our collective breaths for him. Even with a program as proactive as ours, even with the technology available to us with GPS tracking, we can’t protect this bear from careless drivers. Now it’s a waiting game, and we are all rooting for him. But it’s up to all of us—visitors and employees—to take it upon ourselves to remember that the bears of Yosemite spend their lives struggling to fit into our unique dichotomy of our ‘wilderness’ and the millions of people who are inspired by it each year.

Stay aware, drive slowly (Yosemite’s bears have more at stake than a speeding ticket), and if you’re lucky enough to see a bear in the park, take time to appreciate how many challenges it has probably overcome to be where it is. The resilience of wildlife is awe inspiring—even more so as they navigate through a world decidedly trammeled by humans.

Learn more about our bear management team and what you can do to keep Yosemite’s bears wild, and about how to safely interact with park wildlife.