Bear-Resistant Food Storage Lockers

The best way to protect bears and other wildlife from losing their wildness is by preventing them from getting human food and trash in the first place. One of the most important ways you can protect bears in Yosemite is by using bear-resistant food storage lockers consistently and correctly. Taking the time to store food and trash appropriately at all times is the most important way to protect wildlife in Yosemite. Thank you for helping protect Yosemite bears by storing your food and using your bear food storage locker correctly!

A large American black bear laying down eating garbage. Credit: J. Hadley

A little history on the much used, though often overlooked metal box in Yosemite’s campsites.

Bear-resistant food storage lockers were invented in Yosemite in 1977 to provide a safe place for visitors to store food. Prior to these lockers, people attempted various methods to prevent food theft by bears. The most popular food storage method at that time was to put items away inside a vehicle. Unfortunately, for the bears (who injured themselves breaking into cars), and car owners (who not only lost their sustenance but also were hit with the costly car repair), this proved to be a flawed method.

Enter prototype lockers placed in White Wolf Campground on Tioga Road. These steel metal boxes used latches to prevent bears from opening them. With the advantage of thumbs, people could open the box, but bears were locked out. Over the years, latching systems and locker shapes were perfected along with bear-resistant trash cans and dumpsters (with help from the bears showing people the containers weaknesses). These receptacles spread their way across the park and are now some of the most important pieces of infrastructure protecting Yosemite’s wildlife. Innovations in bear-resistant infrastructure have decreased property damage caused by bears from a high of over $659,569 in 1998 to only $2,484 of property damage by bears in 2024. More importantly, food lockers and bear-resistant trash infrastructure have prevented human injury and saved bears’ lives.

What is the biggest problem with food lockers today in Yosemite Valley?

People do not use them correctly or consistently! So far in 2025, bears got into food from lockers 10 times in Curry Village. Most of these incidents were caused by people not closing and latching lockers when they stepped away—whether to the bathroom, inside their tent cabin, or for any other reason. If a locker is not fully latched, food is not safe from bears!

A ranger walks away from an open bear-resistant food storage locker in a campsite after educating campers (behind ranger) to keep the locker closed at all times. Credit: J. Hadley

How do you use a locker correctly?

Food lockers must be kept closed and latched at all times, even if only stepping away for a second! Treat lockers like a refrigerator: open it, remove an item, and close it (and latch it). Anything that a bear may consider food must be stored inside, except for when those items are being used or within arm’s reach. Always pull out on the closed door after latching to ensure it is completely shut and food is safe from bears.

What counts as food that must be stored in a food locker?

For bears, food is anything with a scent or calories. This includes all food, unopened cans, food waste (like corn cobs or watermelon rinds), drinks, condiments, dirty napkins, trash, toiletries, toothpaste, candles, soap, coolers, dirty dishes, and recycling, among other items. All coolers from all companies (even those certified as bear-resistant) must be stored in food lockers at all times.

When should you use a food locker in Yosemite?

While in the front country, food must be stored anytime your food is not within arm’s-reach, in a hard sided building, or an RV with windows and doors closed! All campers must store their food in food lockers. No food is permitted in vehicles overnight (except in hard-sided recreational vehicles). During the day, food may be stored in a vehicle as long as the food or cooler is out of sight and the vehicle is locked with the windows all the way shut. Unfortunately, bears still break into vehicles to get food. Earlier this year, a bear broke into a vehicle causing more than $2,000 in damage to a single car. Anyone backpacking must store excess food they are not taking with them on their hike in shared food lockers that at trailhead parking (backpackers may store food in bear-resistant food container instead of a food locker).

A bear and her cub on a log behind a campsite with a tent and a bear-resistant food storage locker. Credit: J. Hadley

Danger: Bear Trap

Why do Yosemite wildlife biologists capture bears in Yosemite and what do they do when they catch a bear? Wildlife biologists may trap or dart a bear for many reasons, but the most common reason in Yosemite National Park is to manage human-bear conflict. Bears that get human food can start spending time in areas close to people and begin seeking food from humans. These bears lose some of their natural behaviors and may sometimes pose a public safety risk. Capturing a bear gives wildlife rangers tools to help manage and protect both bears and visitors in Yosemite.

A bear trap trailer with a sign “Danger Bear Trap” is parked in a packed parking lot with trees. Credit: J. Hadley

After a bear is caught in a trap, qualified wildlife biologists follow strict protocols developed with National Park Service veterinarians to chemically immobilize the bear with veterinary drugs so the bear can be handled safely. A syringe attached to a pole is used to reach the bear in the trap without endangering park staff. Once the bear is anesthetized, it is carefully removed from the trap using a litter and weighed. The bear is then set down on a tarp to be examined by wildlife biologists. Biologists apply ointment to protect the bear’s eyes and give the bear oxygen through a nasal cannula. The bear’s face is covered to prevent damage to the bear’s eyes and reduce additional stress to the animal.

Biologist prepare to draw a blood sample on an anesthetized bear. Credit: J. Hadley

The most important part of any capture operation is the safety of the bear and park staff. Vital signs are taken at least every five minutes as soon as the bear is removed from the trap to track how the bear is handling the drug. A general health assessment begins: biologists look at the overall physical condition of the bear and check for injuries and parasites. Biologists then check bear claws to note any fraying, which can be an indicator of a bear pulling on man-made objects like the metal of trash or a car. Then body measurements are taken and used along with tooth wear to estimate the bear’s age. The bear’s color and molt status are noted, along with a drawing of any markings (or blazes) on its chest.

A biologist holds a clipboard with a datasheet on it in front of four biologists handling an anesthetized bear. Credit: J. Hadley

Biological samples are taken during the capture for recordkeeping and to further research. Blood and hair are collected for DNA sampling or even can determine how much human food a bear has been eating based on the ratios of isotopes like carbon-13 and nitrogen-15 deposited in tissue. These samples may also indicate diseases the bear has been exposed to like plague or other diseases of interest. Ticks and fleas are collected and preserved for future study.

Biologists estimate a bear’s age by analyzing the wear pattern on its teeth. Credit: J. Hadley

Biologists generally put two identification tags on the bear during the capture, one in each ear. A larger tag (similar to what you might see on a cow) helps biologists identify a bear from a distance, while a smaller yellow tag printed with a four-digit number will likely stay in for much longer and effectively is the bear’s unique identifier for biologists throughout its life. Despite some misconceptions, tag color and numbers have no meaning other than to quickly identify individual animals.

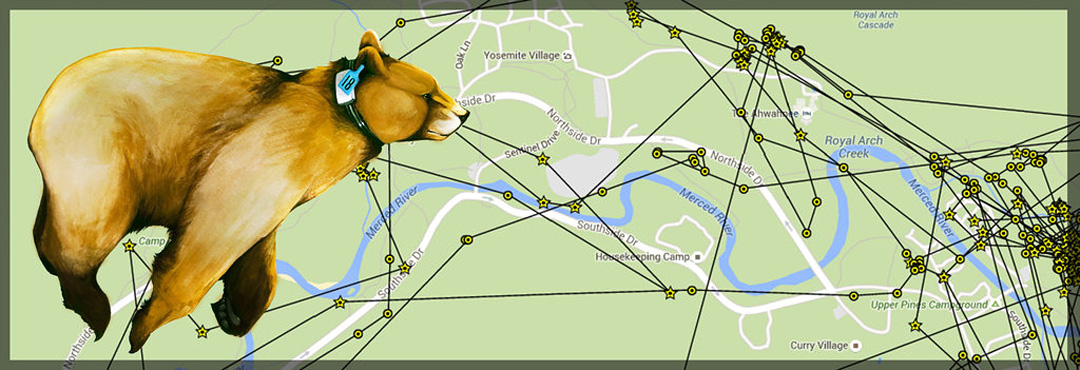

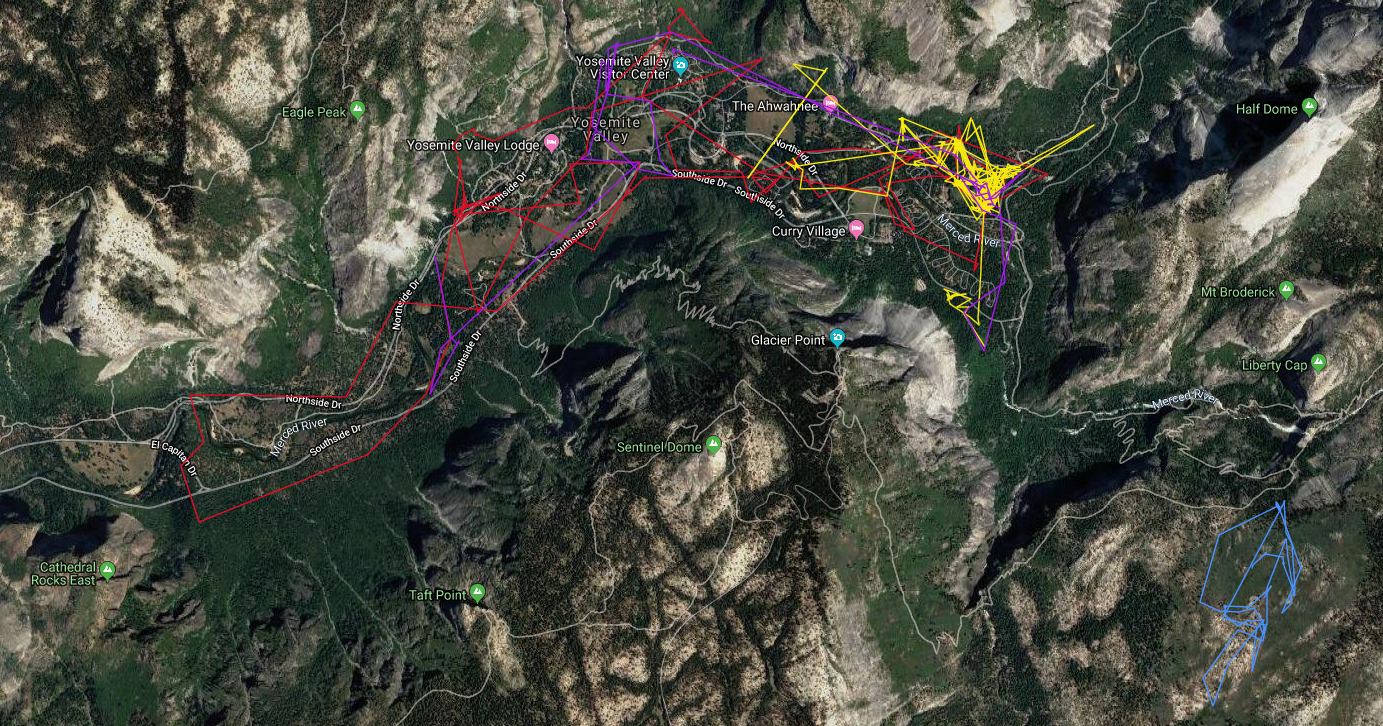

If a bear is a good candidate based on size and weight and how much biologist are concerned about its behavior it may be fitted with a GPS collar around its neck. Since ear tags are only used for identification in Yosemite, they generally do not allow biologists to track bear locations remotely. Instead, GPS collars collect a data point of the bear’s location hourly which is then transmitted to a satellite and accessible for biologists to review every few hours via a website. In a park as big as Yosemite, that can take hours to drive across, the ability to follow a bear’s location from a phone is a huge advantage in helping to keep them from human food and development. GPS collars also have a radio transmitter, which biologists can find and follow using a specialized antenna and receiver in real time in the field. Collars are key in allowing biologists to monitor bears that have started to lose their fear of humans or get human food. Yearlings or bears too small for collars may instead be fitted with ear transmitters that allow for tracking, but do not provide location data. After all the hands-on work is finished, the bear is returned to the bear trap to recover from anesthesia. Once fully recovered, bears are then released back into their home ranges. Moving bears to new areas rarely works. Years of collar data show that bears translocated away from where they were captured almost always return quickly, and Yosemite bears are never moved outside the park.

A dark colored bear with a collar and ear tags in both ears stands in the forest. Credit: NPS/R. Lester

The best part of catching a bear is releasing it from the trap, allowing it to return to being wild and free. While the capture and handling of bears is critically important for wildlife managers to protect people and bears, the best way to protect bears is to prevent them from losing their wildness in the first place. Wildlife professionals carefully weigh the risks that medical procedures like anesthesia (chemical immobilization) pose to a bear—bears are only captured because it allows biologists to prevent conflict that could otherwise be fatal to the bear or cause injury to people. That said, preventing bears from getting human food or becoming comfortable around people in the first place is the best way to protect bears: bear-resistant trash cans and dumpsters save more bears than collars or tags, along with keeping your distance and giving bears respect as wild animals. Less than 10% of Yosemite bears will ever be collared and most Yosemite bears are wild and are never captured. In the best-case scenario, biologists never have to capture bears at all.

A large bear emerges from an open trap wearing a GPS collar. Credit: J. Hadley

Bear Awakening

(Photo: J. Hadley)

Bears are up and moving in Yosemite National Park! They have been spotted moving around from the Sierra Nevada foothills to Tuolumne Meadows in the high Sierra. Bears typically emerge from hibernation in March or April in Yosemite depending on food availability, elevation, and weather. Adult male bears awaken first, followed by solo females and juveniles, and finally sows with cubs. In mid-May, the first spring cubs were spotted in the park on the Yosemite Falls Trail.

The newly awakened bears are hungry! Bears in Yosemite Valley eat new grasses, flower buds, and fresh roots in the early spring along with leftover natural food (especially black oak acorns this year) from the previous fall. Bears also use meadows and vernal pools to consume new sedges high in sugar. As spring progressed, bears were observed tearing into decaying logs looking for insects and nests. In June, bears began eating fruit including white stemmed raspberries and non-native apples. Despite the fresh growth available as food, Yosemite bears can continue to lose weight into May while their metabolisms recover from hibernation.

Besides working on regaining weight lost in hibernation, multiple male bears were observed following female bears around starting in early May. This seems early as the courtship of sows by boars (mating season) usually does not begin in the Sierra until early June. Sows will aggressively chase off their yearlings this time of year before coming into estrus and mating. The only female bear seen with a yearling in Yosemite Valley was last observed together prior to separating in the first week of May. While black bears mate in late spring or early summer, the fertilized egg does not implant until fall to make sure the female’s body condition can support a pregnancy to term.

How can you help protect these bears this summer? The same things we need to do every day to keep bears alive and wild! Store food and trash (anything with a scent or calories) within arm’s reach of an awake person or secured in a building, bear canister, or food locker. Stay a minimum of 50 yards away from bears and further if your presence is changing their behavior.

Bear Ahead!

Photo Credit: Drew Wharton

Photo Credit: Drew Wharton

Photo Credit: Drew Wharton

For bears, their natural fear of people is an important instinct that keeps them safe. When a bear becomes habituated, losing its natural fear of people, other behaviors can change and dangerous situations can evolve with people. This is why rangers staffed these areas from late August through November. Rangers also created a fun new display to show people exactly how far they should be from a bear: a fun wooden bear silhouette designed to stand a 50 yards down a trail from a sign with bear information on it. This sign explained what to do if you see a bear, and demonstrated exactly how far visitors should remain from bears in order to help keep them wild. All these efforts, as well as the interest that visitors took to learn and understand their role in protecting wildlife in national parks, helped make a difference in these acorn eating bear’s lives.

HEY BEAR, HI BEAR, GO BEAR!! How and when to scare away a bear in Yosemite.

Here’s the situation: you are hanging out at your campsite or on a picnic area beach in Yosemite, when you hear a branch crack behind you. You turn around to find a bear approaching. What do you do?

You stand up, face the bear, wave your arms, and yell at the bear. We mean YELL at the bear, as loudly as you possibly can. Be aggressive with your voice and body language. You’re not just making noise; you’re scaring a bear away! You have to mean it for it to work.

Here are some examples of things you can yell:

HEY BEAR!!

GO BEAR!!!

GET OUT OF HERE BEAR!!

Or even just: AHHHHHHHHHHHHHH BEAR!!!!!!!!!

One half-hearted yell may not be enough to scare a bear. So, keep yelling LOUDLY and AGGRESSIVELY until the bear leaves. Yell, clap your hands, wave your arms, hit a stick against a tree, get other people to help you yell! You can even throw small objects like pinecones or small pebbles at the bear to help scare it. (You’re trying to gently hit the bear with the pebble or pinecone—not injure it: Bears don’t like being touched.) Don’t chase the bear; just use your voice to scare it away.

Do you have time to snap a quick picture? No!

Do you have time to look around for a pot to bang or a whistle to blow? No! Use your voice! Your voice is your most effective tool to scare a bear away (and you don’t have to go looking for it… unless you’re really scared).

When a bear is around people, it could be only moments away from getting food, so you need to make it feel unwelcome immediately. Once a bear is eating food, it will be harder to scare away and much more likely to return in search of more food, ultimately getting itself into more trouble. We also want bears to be immediately afraid of people (as they naturally are), rather than assuming most people aren’t scary.

Bears that consume human food typically have decayed and damaged teeth. But that’s not the only negative consequence: when a bear gets food from people, even just a banana, the bear will change its natural behavior. Bears are extremely food-driven and a bear that gets human food will often become so bold in its attempts at getting human food that it has to be killed to protect people. So, when you see a bear approaching you or in any developed area (e.g., campground, picnic area, trail, parking lot), it is important to scare it away immediately, stopping this cycle, and helping keep the bear wild and alive. Yes, yelling at a bear helps keep it alive.

What about when you see a bear in a meadow, in the wilderness, or anywhere else away from human development or people—should you scare it? Generally, no. Do you have time to snap a quick picture? Probably, if you are at least 50 yards away from the bear. It can be one of the best Yosemite experiences getting to watch a wild bear do wild bear things.

Are you having trouble envisioning scaring a bear away? This video shows what it sounds and looks like. This advice applies in Yosemite; always check local recommendations when visiting bear country.

Speeding Kills Bear

Photo Credit: NPS

Four Bears Hit by Vehicles in Yosemite this Month

Black bear mother and cubs (Photo: Robert G. Lester)

In the last three weeks, at least four bears were hit by cars in Yosemite, at least two of which were killed. The two bears that survived were hit by drivers going faster than the 25 mph speed limit and were seriously injured and limping. We will never know the severity of their injuries. It is important to remember that while traveling in the park, the posted speed limits are not only there to protect people, but to also protect wildlife in areas where animals cross roads. Following posted speed limits may save the life of a great gray owl as it flies across the road, or a Pacific fisher as it runs across the road, both of which are endangered species. This easy action—slowing down—may also prevent you from hitting a bear eating berries on the side of the road, or a deer crossing with its fawn. While traveling through Yosemite, try to remember that we are all visitors in the home of countless animals, and it is up to you to follow the rules that are put in place to protect them.

Have you ever noticed the signs by the side of the road that say, “Speeding Kills Bears” with the image of a red bear on them? These signs mark the locations of bears where they have been hit by a vehicle this year, or where bears have been frequently hit in previous years. We take these signs down each winter and put them up as the accidents occur, hopefully as a reminder to visitors to slow down and keep a lookout for wildlife. If you do hit an animal while in Yosemite and need immediate ranger response, you can report it to the park’s emergency communication center at 209/379-1992, or by leaving a message on the Save-A-Bear Hotline at 209/372-0322 if you believe that the animal is uninjured. You may also use the Save-A-Bear Hotline number to report non-urgent bear observations.

Do Yosemite Bears Hibernate?

It’s a simple fact that black bears spend their whole life following their stomachs, including in winter. Similar to the postman’s motto, “neither snow, nor rain, nor heat, nor gloom of night,” keeps a bear from eating its fill. So for bears in Yosemite, winter denning is not associated with the weather so much as it is linked to food availability. There are years when oak trees make an over-abundance of acorns, considered a mast year, and bears can been seen all winter digging under feet of snow to feast on acorns. Similarly, it has been reported in other areas that bears will rouse from winter dens to take advantage of trash cans that are put out curbside every week on trash day. So while bear behavior can be motivated by both human and unnatural foods, it is not uncommon to find bear tracks in the snow and it is important to always lock up food in a hard-sided structure or in a food locker when visiting Yosemite.

Picture taken recently from the Yosemite Museum of a bear in the snow.

Recent tracks of several bears still active in Yosemite Valley despite winter storms.

The Scoop on Bear Poop

Scat (Photo: NPS)

You are walking along outside when you come upon a large pile of poop. How can you tell if it’s bear poop? Given the variation in their diets, bear scat from one bear can look very different from another bear. Poop from the same bear may look entirely different on different days. So, how can you tell?

Grass scat (Photo: NPS)

Black bears are omnivores and eat a wide range of foods including grass, roots, fruit, insects, fish, and animal carcasses. Their digestive system is similar to a human’s; they have a stomach and a small and large intestine. Some things will digest in the bear’s stomach and won’t be visible in the scat, while other things, like apple peels, seeds, fur, and bones will be present in the poop. Black bear poop can take on many shapes. The color and composition of their poop will change with the seasons, as does their diet. In the spring, bears eat a lot of grass and insects, so their poop is often green and tubular, with grass visible. In the late summer and fall, bear poop will be looser and in large plops, with berries and apple pieces visible.

Berry scat (Photo: NPS)

What other types of poop may you come across? Here in Yosemite, you may stumble upon coyote, raccoon, mountain lion, or bobcat poop, all of which can be confused with bear poop. Coyote poop is also tubular and may contain the same foods, but it usually looks like a pile of twisted rope. Raccoons go to the bathroom in the same spot over and over, so their poops will be found in large piles called latrines. Bobcats and mountain lions both have segmented poops, a characteristic common to felines. Their poop is dense and won’t flatten if you step on it. All of the poop piles mentioned above are smaller than a bear’s.

Scat (Photo: NPS)

Well, now that you’ve got the data on the scat-a, go out and find some bear poop!

Yosemite National Park Designates Wildlife Protection Zones Throughout the Park

This image shows one of Yosemite National Park’s newly designated Wildlife Protection Zones and the associated sign that motorists will see along roadways while driving through Wildlife Protection Zones in Yosemite National Park. NPS Photo.

Speed Enforcement in Effect to Help Protect Bears and Other Wildlife

In preparation for a busy Labor Day Weekend, Yosemite National Park has designated several new Wildlife Protection Zones located on stretches of roadway throughout the Park where bears and other animals have been hit by vehicles. Visitors driving in the park this weekend will see new signs advising motorists that you are in a “Wildlife Protection Zone” and that speed limits will be strictly enforced. Multiple zones have been designated in Yosemite Valley and along sections of Big Oak Flat Road, El Portal Road, Wawona Road and Tioga Road. These zones will remain in effect until further notice.

As of August 28, 2019, 11 bears have been hit by vehicles during the 2019 calendar year. More than 400 bears have been hit by vehicles in Yosemite National Park since 1995. It’s not just bears that face the danger of being hit by a vehicle on roads within Yosemite National Park. Owls, Pacific fishers, butterflies, rare amphibians like red-legged frogs and salamanders; and mammals like deer, foxes, and mountain lions are also often hit and killed on Yosemite’s roads.

“One of the best ways to help protect wildlife in Yosemite National Park is to slow down and follow the posted speed limits within the park,” stated Yosemite National Park Superintendent Michael Reynolds. “These new Wildlife Protection Zones have been designated to help reduce the number of animals injured or killed in the park by automobiles. We thank park visitors for helping us protect Yosemite’s bears and other wildlife.”

How can park visitors help protect wildlife while driving in and around Yosemite National Park? Please stay alert, especially while driving during dawn and dusk, when animals are more active. Scan roadsides for wildlife in front of your car and obey posted speed limit signs including areas with reduced speeds. These small actions can help make a big difference and help prevent wildlife-automobile collisions.

-NPS-

Editor’s Note: The attached photo is an NPS Photo and may be published in print and electronic media. Please list the photo credit as “NPS Photo.”

Media Contacts:

Scott Gediman 209-372-0248

Jamie Richards 209-372-0529