National parks exist to protect wild and inspirational places, unimpaired, for this and future generations—to create the opportunity for people to experience these regenerative natural places, for the most part, as they would be without the impact of human development. But for wild animals, even our short visits to observe and recreate can have immense effects.

It’s early summer, and calls are flooding into the save-a-bear hotline. “A bird is stuck in our foyer,” “There’s a rattlesnake by my front porch,” and “How do I get a squirrel out of my Sprinter van,” interspersed with the occasional “There’s a bear in the meadow about 20 minutes from here.” With limited resources and staff, we prioritize our responses by how urgent calls seem to be, and when we first heard about this bear, it sounded fairly innocuous—there’s a bear in the meadow about 20 minutes from here in an area marked by meadows overflowing with the young grasses that bears depend on in the spring. It wasn’t until a couple of weeks later that we were told how close the bear had been getting to park visitors. Apparently, he had sauntered within five feet of people multiple times. If this bear was to remain wild, we had to act immediately.

Within a day, a team of wildlife biologists, technicians, and volunteers were heading out on a darting mission for the bear. By five o’clock that night, the bear, an adult male, was located, darted with a sedative, and fitted with a GPS collar: one of our most effective tools in the constant battle to keep Yosemite’s bears safe and wild.

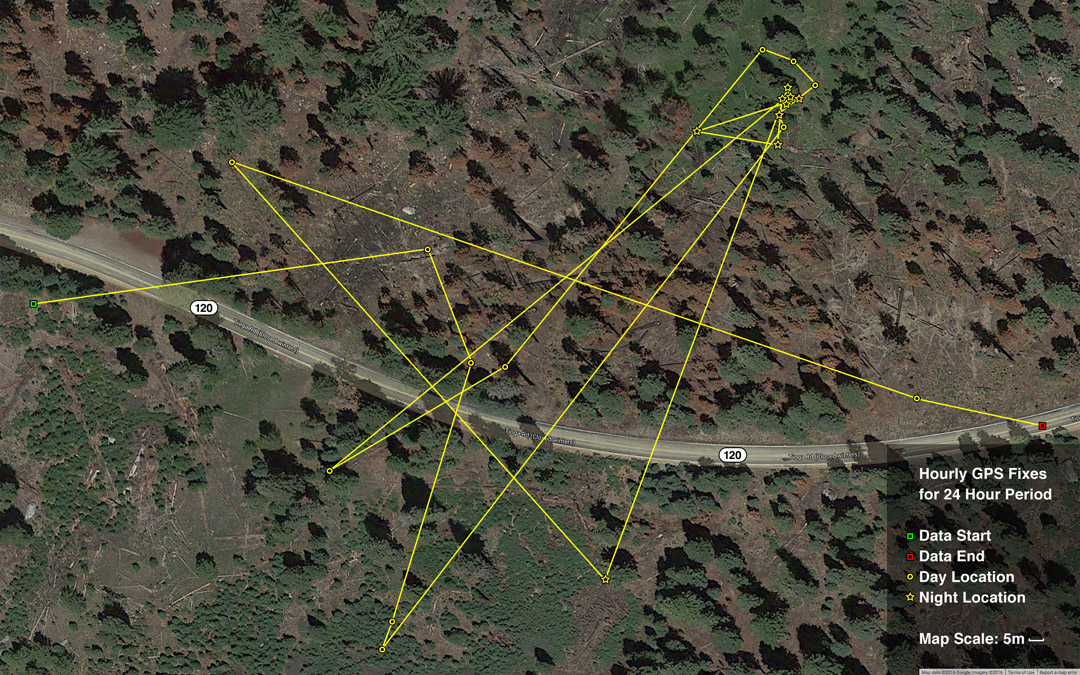

Bears are incredibly intelligent animals, and this one is no exception. He had been spending time closer and closer to human development. Without any negative repercussions, he had been losing his natural fear of humans—becoming “habituated” to human presence. Once bears become habituated, the likelihood of them being involved in conflicts with people skyrockets— which puts us (and the bear) into bad situations. This is why collaring this bear quickly was so vitally important: Once he was collared, we could keep track of his movements (hourly!) and scare him away whenever he came near human development.

We got to this bear in time. Our intense efforts to reinstill his fear of humans were successful. If he had been fed by visitors, we may not have been so lucky. This bear hasn’t been near campsites or human development at all recently. But for him, it may have been out of the frying pan and into the fire. Today, watching his movements via the data from his GPS collar, we are seeing a surprising trend since he gave up on development: Possibly because of all of the seed-producing trees and grasses that grow in edge ecosystems, he has been spending all of his time on the roadsides of one of the busiest roadways in the park.

Somehow, this bear has crossed this major road hundreds of times since his capture in June. With 27 bears hit by vehicles in the park last year, this realization shocked us, and I think we are all holding our collective breaths for him. Even with a program as proactive as ours, even with the technology available to us with GPS tracking, we can’t protect this bear from careless drivers. Now it’s a waiting game, and we are all rooting for him. But it’s up to all of us—visitors and employees—to take it upon ourselves to remember that the bears of Yosemite spend their lives struggling to fit into our unique dichotomy of our ‘wilderness’ and the millions of people who are inspired by it each year.

Stay aware, drive slowly (Yosemite’s bears have more at stake than a speeding ticket), and if you’re lucky enough to see a bear in the park, take time to appreciate how many challenges it has probably overcome to be where it is. The resilience of wildlife is awe inspiring—even more so as they navigate through a world decidedly trammeled by humans.

Learn more about our bear management team and what you can do to keep Yosemite’s bears wild, and about how to safely interact with park wildlife.